FRANKINCENSE REVISITED, PART II

Introduction

Frankincense has been a valued commodity for millennia, prized for its pleasant scent and burnt as an offering to the gods of many different religions. From Ancient Egypt to Judaism, from the Roman Empire to the modern Catholic Church, but also in China, Japan, and India, frankincense was and is a traditional incense material and is also used as a natural remedy for various ailments [1 – 4]. The material is a gum resin sourced from the genus Boswellia and traded as such in various quality grades as well as in form of the distilled essential oil.

In part I of this study, the volatile and semivolatile composition of the gum resins originating from the four commercially most important Boswellia species, namely B. sacra, B. serrata, B. papyri/era, and B. frereana, were analyzed and discussed. Part II continues this investigation with a focus on less common Boswellia species and two samples from hybridization experiments.

The Island of Socotra, located at the entrance to the Gulf of Aden between Somalia and Yemen, harbors seven endemic Boswellia species [5]: B. ameero BALF.F., B. bullata THULIN, B. dioscoridis THULIN, B. elongata BALF.F., B. nana HEPPER, B. popoviana HEPPER, and B. socotrana BALF.F., three of which are treated in this study and have not or only rarely been investigated. In addition to these, B. rivae ENGL. and B. neglecta S. MOORE from Africa were analyzed.

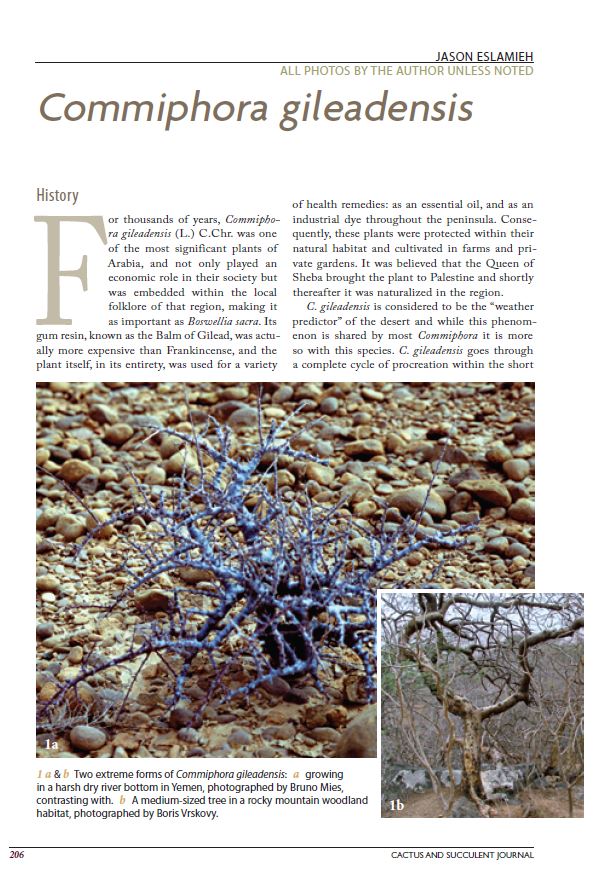

COMMIPHORA GILEADENSIS

For thousands of years, Commiphora gileadensis (L.) C.Chr. was one of the most significant plants of Arabia, and not only played an economic role in their society but was embedded within the local folklore of that region, making it as important as Boswellia sacra. Its gum resin, known as the Balm of Gilead, was actually more expensive than Frankincense, and the plant itself, in its entirety, was used for a variety of health remedies: as an essential oil, and as an industrial dye throughout the peninsula. Consequently, these plants were protected within their natural habitat and cultivated in farms and private gardens.

It was believed that the Queen of Sheba brought the plant to Palestine and shortly thereafter it was naturalized in the region. C. gileadensis is considered to be the “weather predictor” of the desert and while this phenomenon is shared by most Commiphora it is more so with this species. C. gileadensis goes through a complete cycle of procreation within the short monsoon period: it leafs out, flowers, gets pollinated, sets seeds and disburses those ripened seeds all within the few months of the monsoon season. As the monsoon rolls out, the trees lose their leaves, remaining leafless for most of the year until the next monsoon season. Occasionally when there is a rise of heat, humidity and low barometric pressure, the plants will leaf out off season but it is unknown if they produce flowers.

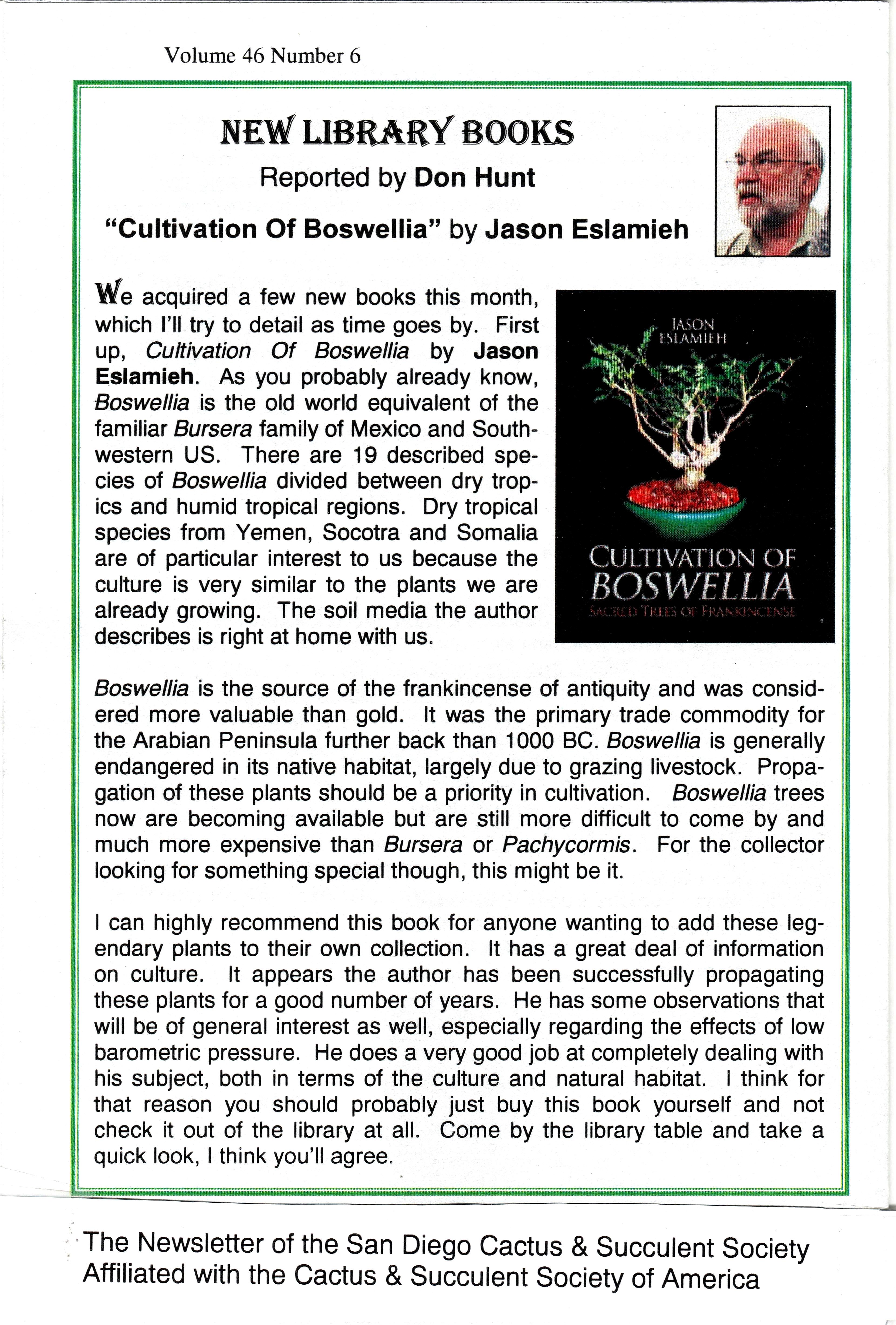

BOOK REVIEW

BOOK REVIEW 2

Eslamieh, J, Cultivation of Boswellia. Sacred trees of frankincense

A Book’s Mind, Phoenix, [15 Mar] 2011.

ISBN 978 0 9828751 1 7. Price $32.99 (£20). Available from specialist booksellers, or from www.Jason-Eslamieh.com.

viii, 196 pages, 218 colour photos, 13 graphics; 24.2 × 19.1cm., softbound with colour photo covers.

Introduction to the 19 species and 6 cultivars of Boswellia.

Like me, most of you probably have not heard of Boswellia. They are related to Bursera, which you may well have heard of or grow already. They come from tropical Africa, the Arabian Peninsula and India, and seven of the species are endemic to the island of Socotra. They are best known for the gum resin frankinsense that is extracted, mainly from Boswellia sacra. It has been used as a medicinal and beauty product and was prized for its aromatic incense from ancient times, having a long association with religious ceremonies.

From the horticultural point of view they make very attractive bonsai subjects, but are not very succulent and require more warmth than most growers can financially justify. This also restricts the availability, so only a few species are usually available from specialist nurseries.

This book tells you more or less everything you will ever need to know about boswellias, and the author gives generously of his cultivation experience. The requirements are similar to those for succulents generally, and the author stresses a low pH, well-drained but moisture-retentive compost. They can withstand drought for a few weeks, but drop their leaves in response to it, and it will check the growth. They are better grown continuously with the compost never completely drying out. In pots, daily or even more frequent watering is recommended for plants in full growth.

Flowering and pollination are strongly influenced by air humidity, and the author offers the interesting idea that the plants are sensitive to atmospheric pressure, quoting results from NASA experiments. Propagation is from seed or stem or root cuttings, and 25-32ºC is needed for success.

Even if you never grow boswellias, you might well still consider buying this book for its cultivation advice and hints on such subjects as showing, which are applicable to the management of a wide range of tropical bonsai succulents.

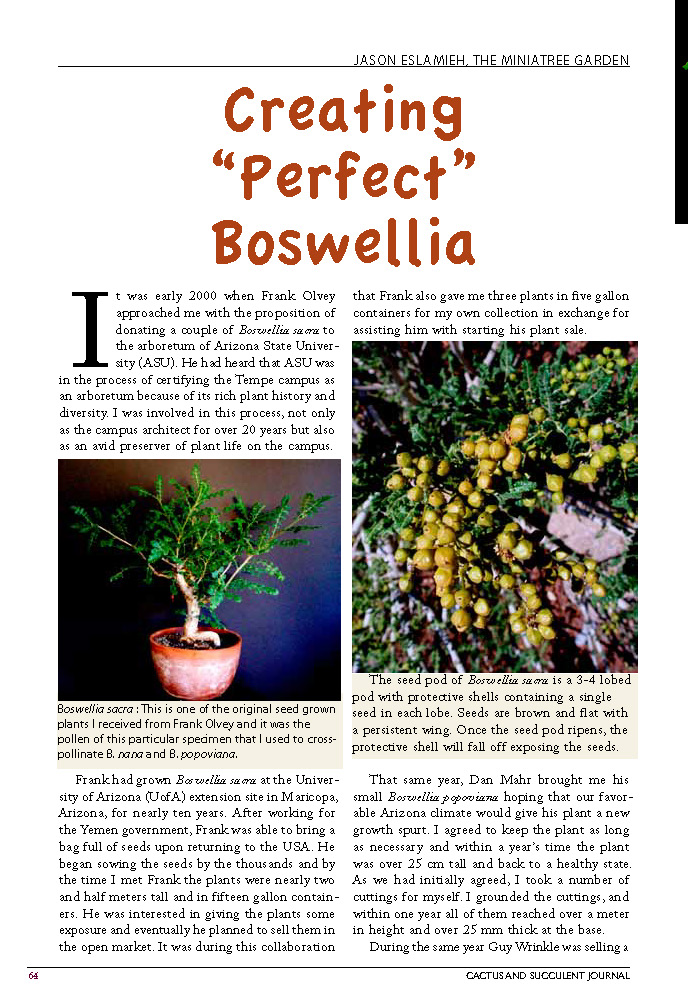

CREATING “PERFECT” BOSWELLIA

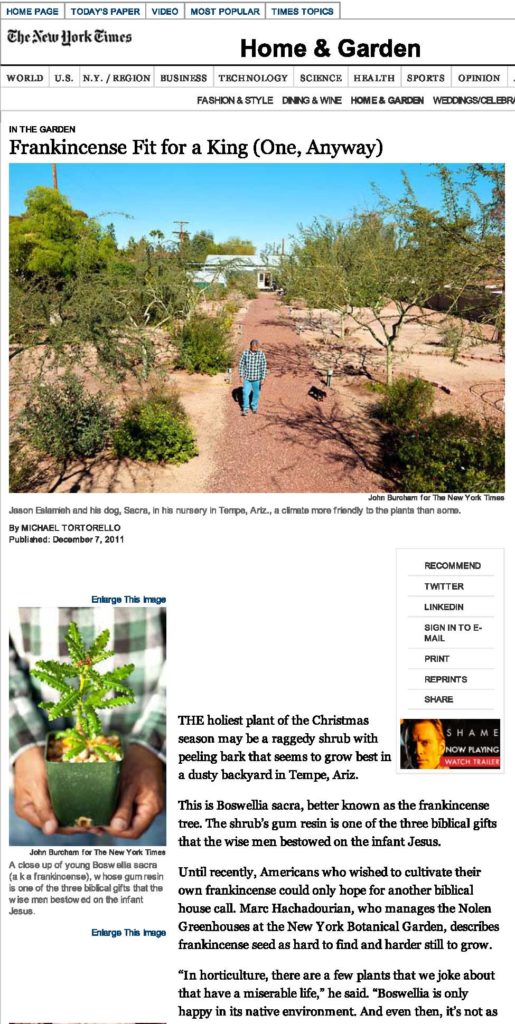

It was early 2000 when Frank Olvey approached me with the proposition of donating a couple of Boswellia sacra to the arboretum of Arizona State University (ASU). He had heard that ASU was in the process of certifying the Tempe campus as an arboretum because of its rich plant history and diversity. I was involved in this process, not only as the campus architect for over 20 years but also

as an avid preserver of plant life on the campus. Frank had grown Boswellia sacra at the University of Arizona (UofA) extension site in Maricopa, Arizona, for nearly ten years. After working for the Yemen government, Frank was able to bring a bag full of seeds upon returning to the USA. He began sowing the seeds by the thousands and by the time I met Frank the plants were nearly two and half meters tall and in fifteen gallon containers. He was interested in giving the plants some exposure and eventually he planned to sell them in the open market. It was during this collaboration that Frank also gave me three plants in five gallon containers for my own collection in exchange for assisting him with starting his plant sale.

THE HETEROSIS OF OPERCULICARYA

Operculicarya (O.) species have been praised by growers, collectors, and exhibitors for decades. It seems that almost

all of the species are considered great subjects for staging and are highly desirable because of their care-free nature. The

incredible diversity amongst them ranges from tree form to true caudiciform, each with its own set of unique characteristics making this small genus of Anacardiaceae unquestionably a gem in any greenhouse or garden.

Perhaps by presenting a short history and description of these species, including actual photos and herbarium material, prior to discussing the hybridization and heterosis traits of this genus, would provide a fundamental understanding of the genus and the vocabulary used to analyze the hybrid vigor of the new species. I must say that the new information on some of the latest described species is inadequate to truly understand or to be able to draw an accurate morphological picture of these species. Furthermore, it appears that the data of some of the recent descriptions are not tested and claims are based on partial information. Nevertheless, what is available now is more than what we had previously; this should open the door for dialogue and ultimately result in more accurate information.

Eight of the nine described Operculicarya species are endemic to Madagascar, but O. gummifera grows in two of the Comoro islands as well. Perrier de la Bathie initially described Operculicarya decaryi, O. hyphaenoides, and wrongly, O. monstruosa in 1946. He named the new genus due to the presence of opercula in the bony endocarp. Gradually, additional species were discovered and added to the genus making up the nine species that are described below.